Ruby-us Hagrid: Writing Harry Potter with Ruby

Hi there 👋! Here are my extended notes for the talk I gave at Brighton Ruby 2018, and RubyConf 2019.

Introduction

This is a talk based around a big idea: using Ruby to write a brand new Harry Potter story, completely automatically. Whether we’re embarking on this journey for self-enlightenment, or to grab a slice of J. K.’s billions, along the way we’ll see first-hand the power and elegance of Ruby for tackling problems in the field of natural language processing.

Let’s get straight to the “good part”: what does our final program look like, and what kind of quality can we expect from the Harry Potter stories it generates? Here’s a minimal implementation of our final model (a 4-gram model using a weighted random algorithm/maximum likelihood approach for choosing continuations - don’t worry if that sounds like gibberish for now!). For the minimal version, we haven’t worried about things like testability, object orientedness etc.

def tokenize(sentence)

sentence.downcase.split(/[^a-z]+/).reject(&:empty?).map(&:to_sym)

end

def pick_next_word_weighted_randomly(head, stats)

continuations = stats[head]

continuations.flat_map { |word, count | [word] * count }.sample

end

text = tokenize(IO.read('hp.txt'))

stats = {}

n = 3

text.each_cons(n) do |*head, continuation|

stats[head] ||= Hash.new(0)

stats[head][continuation] += 1

end

story = stats.keys.sample

1.upto(50) do

story << pick_next_word_weighted_randomly(story.last(n - 1), stats)

end

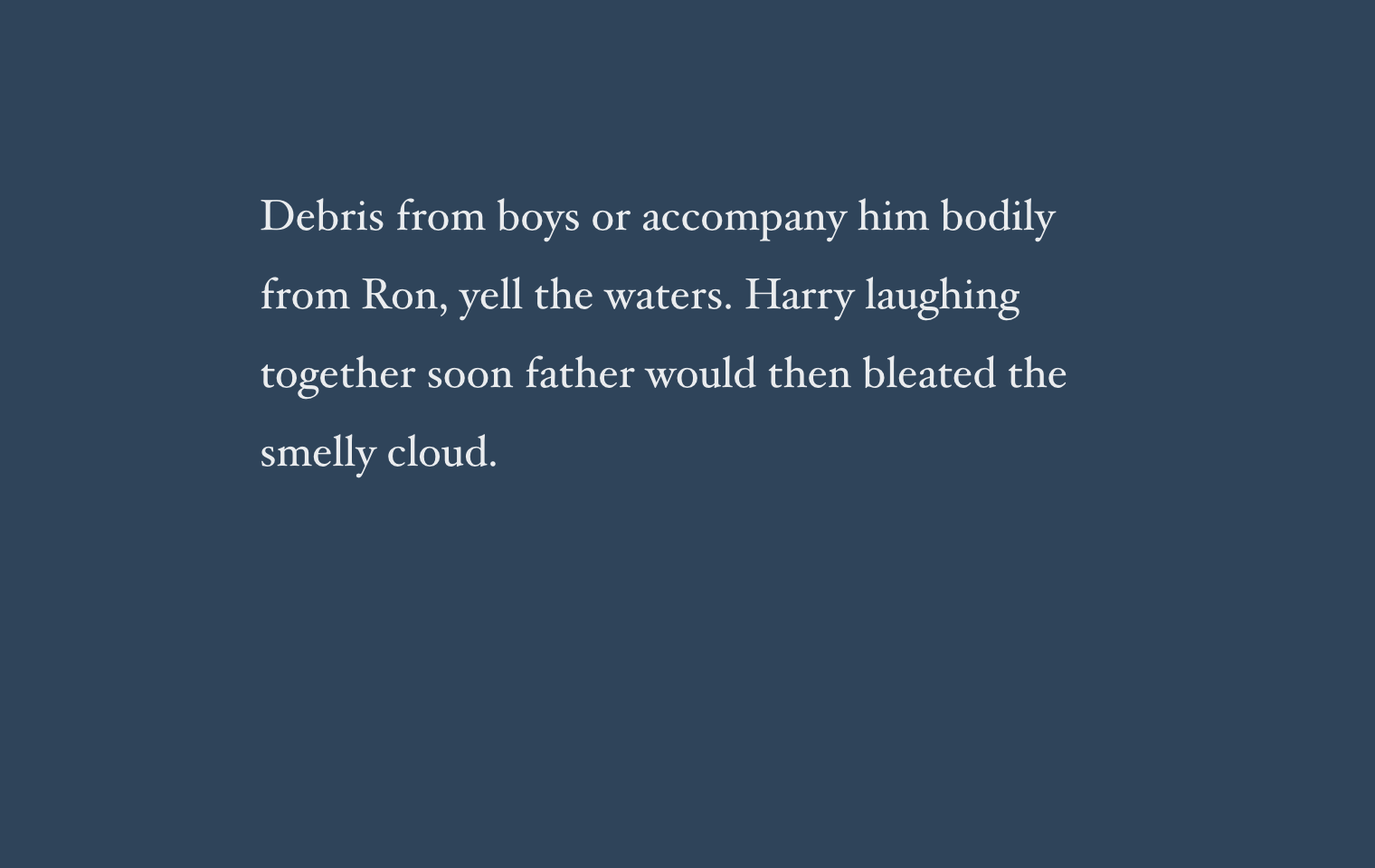

puts story.join(" ")And here’s an example output from the program. (Note: I’ve added punctuation, and also done some heavy cherry-picking to show off one of the better runs, but otherwise the output is untouched).

If you’d like, study the code above, and try and see if you can understand what’s going on. Or alternatively, read on as I reveal the Dark Arts of the program’s inner workings…

iPhone inspiration

As developers, we’re trained to take a large problem and break it down into smaller sub-problems. However, if you’re like me, when faced with the problem of telling a story (or even generating a coherent sentence) your first reaction might be “Where on earth do I start?“.

There’s an old army proverb: “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.” In a similar fashion, the secret to making the problem of generating our Harry Potter pastiche manageable is to focus on generating it one word at a time. That is, our program will work iteratively, and at each iteration it will extend our story by a single word (ideally, in such a way that the end result is coherent and Rowling-esque).

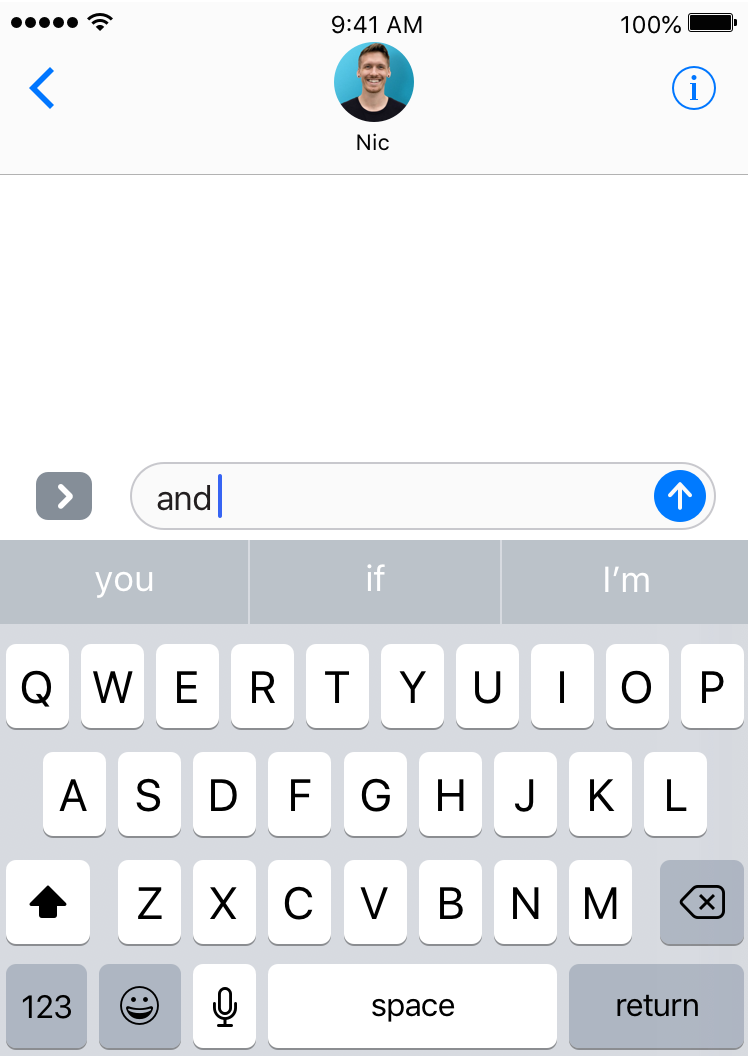

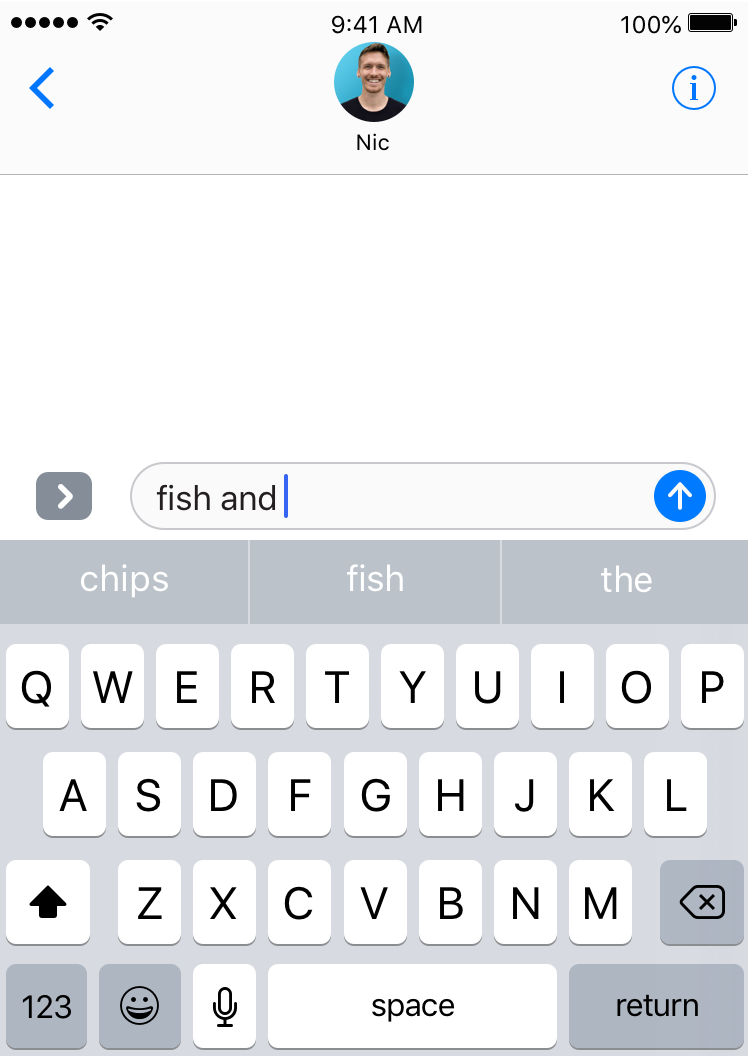

Thinking in these terms, it turns out we have an amazing source of inspiration closer than we think (there’s a good chance it’s sitting in your pocket right now) - our smartphones. All modern smartphones come equipped with a predictive keyboard. Although we generally treat predictive keyboard as a typing aid, they can also be a surprisingly effective way to generate language. In the recording I took from my phone below, I repeatedly hammer the middle prediction button - have a look at the output it generates:

My predictive keyboard, (ab)used in such a way, becomes a surprisingly good language generator - that sentence could easily have been written by a human. What’s more, my predictive keyboard, through years of me using my phone, has learnt my style of writing; the words it suggests are based on my patterns of language use, so the generated sentence, in some ways, “sounds like me”. This is why predictive keyboards are of such interest to us: if we can understand how my phone is able to imitate my style of writing, we can apply the same principles to write a Ruby program to imitate the style of J. K. Rowling/the Harry Potter books.

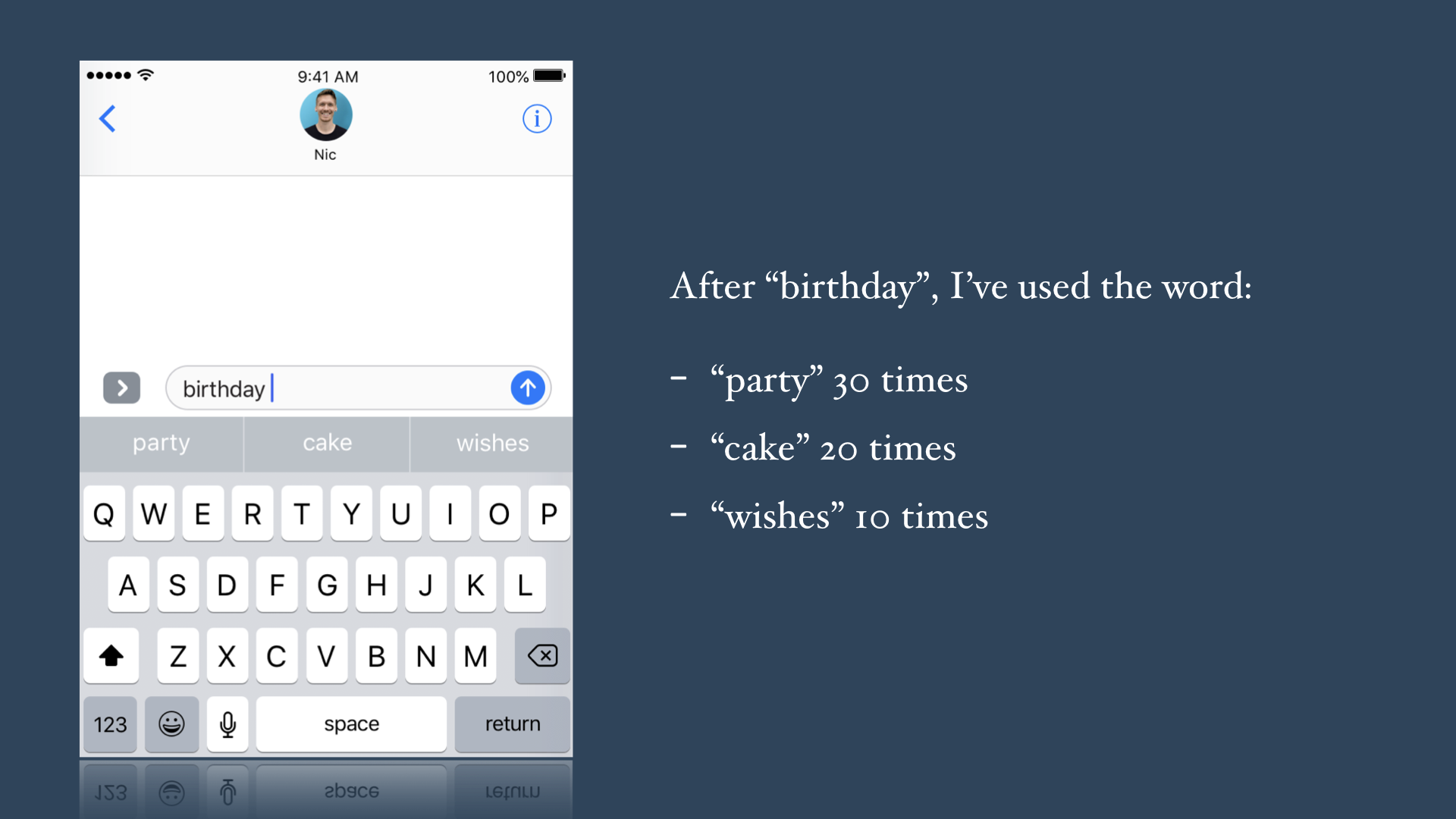

So how does my phone learn my style, and offer predictions tailored to me? Fundamentally, it comes down to counting: my phone counts the words I use most frequently in a given context. For example, buried somewhere in my phone’s memory are stats like this:

My phone knows that after “birthday”, I used the word “party” more frequently than any other word, so that’s the predictive keyboard’s #1 suggestion. “cake” and “party”, my 2nd and 3rd most frequently chosen follow-on words for “birthday” are accordingly offered as the #2 and #3 suggestions.

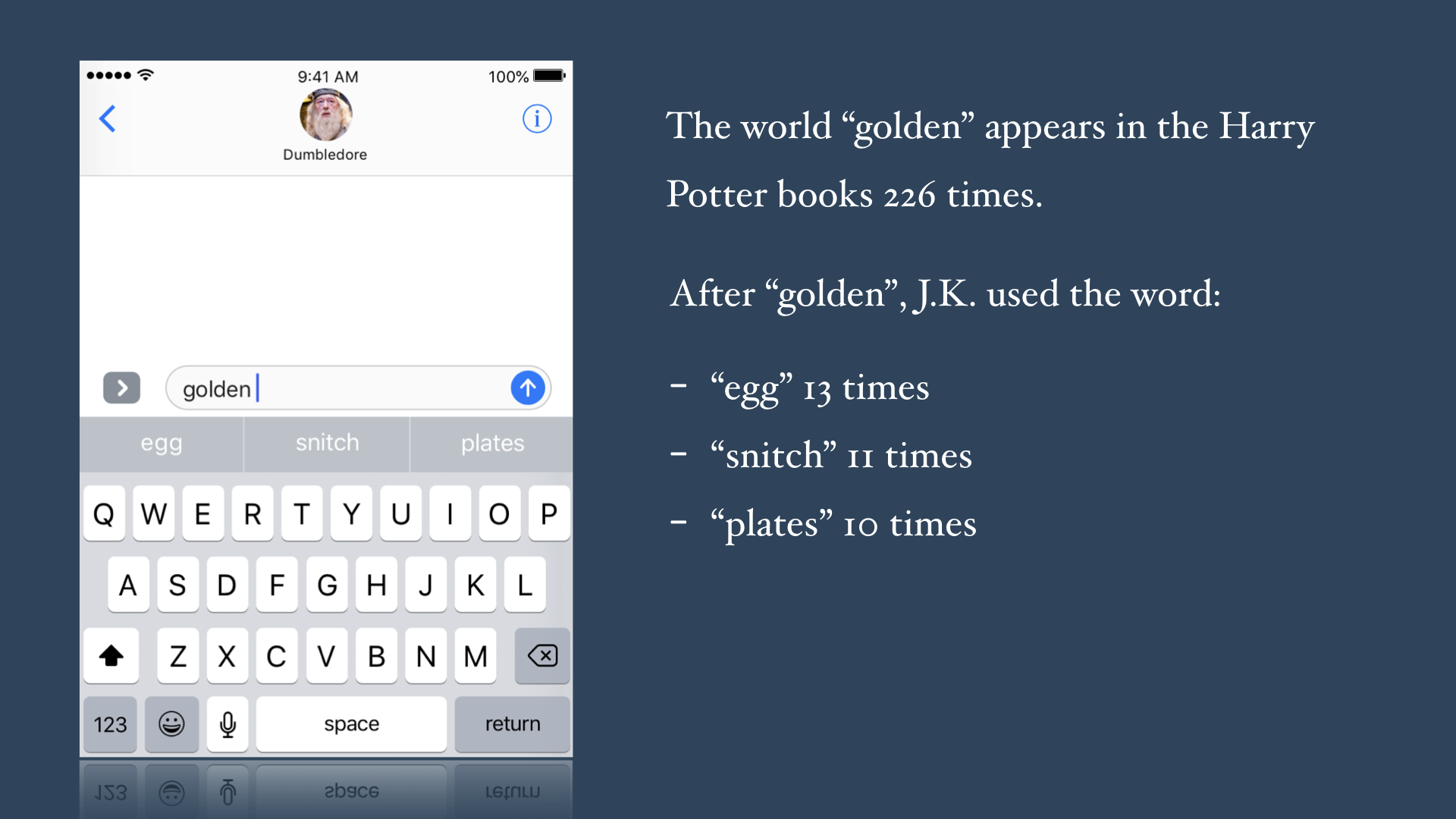

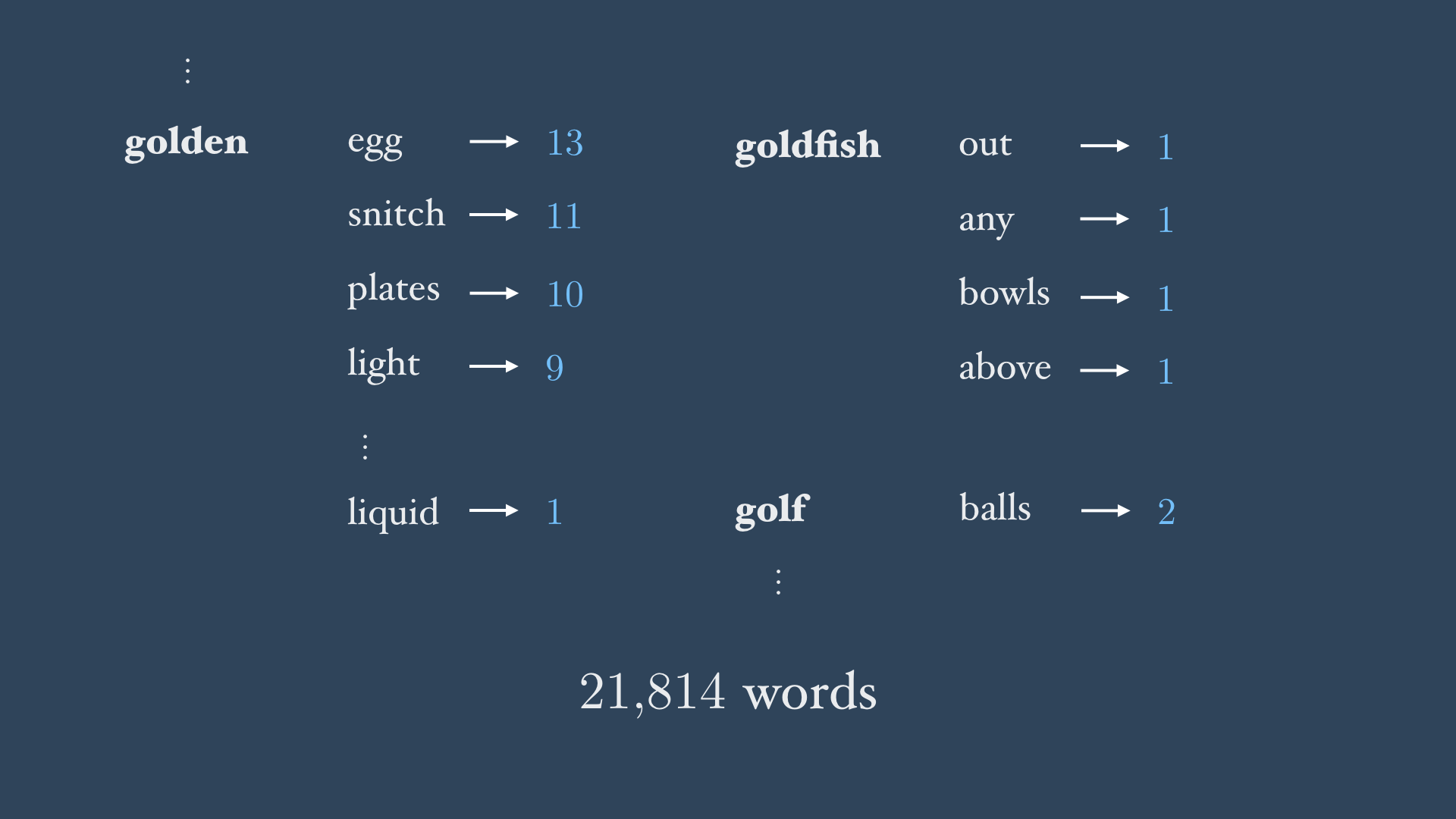

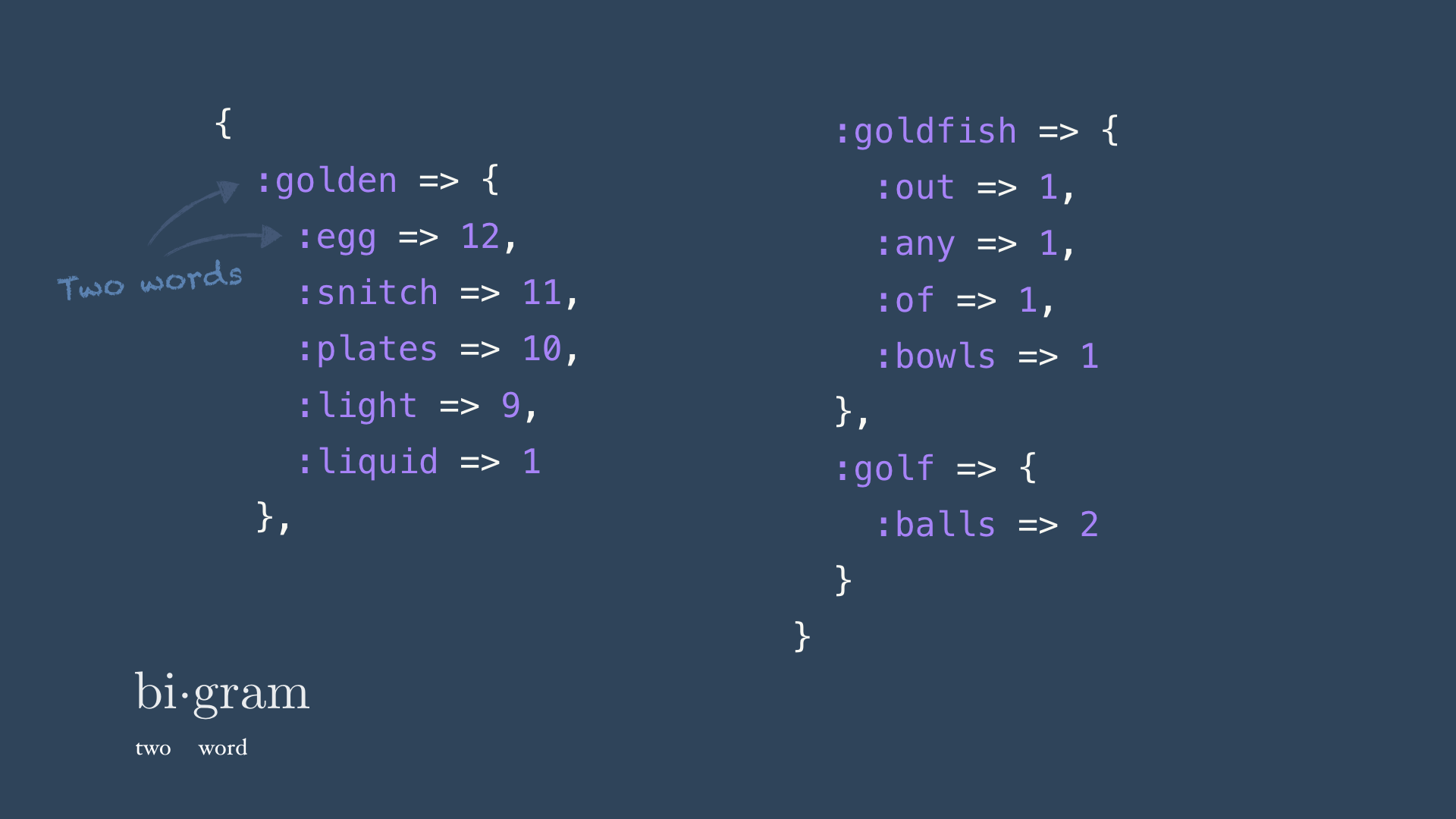

How could we build a predictive keyboard trained on the Harry Potter books? (In fact, that’s exactly what Botnik Studios did, yeilding amusing results). Well, for any given word, we just need to enumerate the words that are used directly after that word, and how many times each is used. For example, consider the word “golden”:

The word “golden” is followed most frequently by “egg” in the series (the phrase “golden egg”, a key element in the Triwizard tournament, appears 13 times) followed by “snitch” (appearing 11 times) and “plates” (10 times).

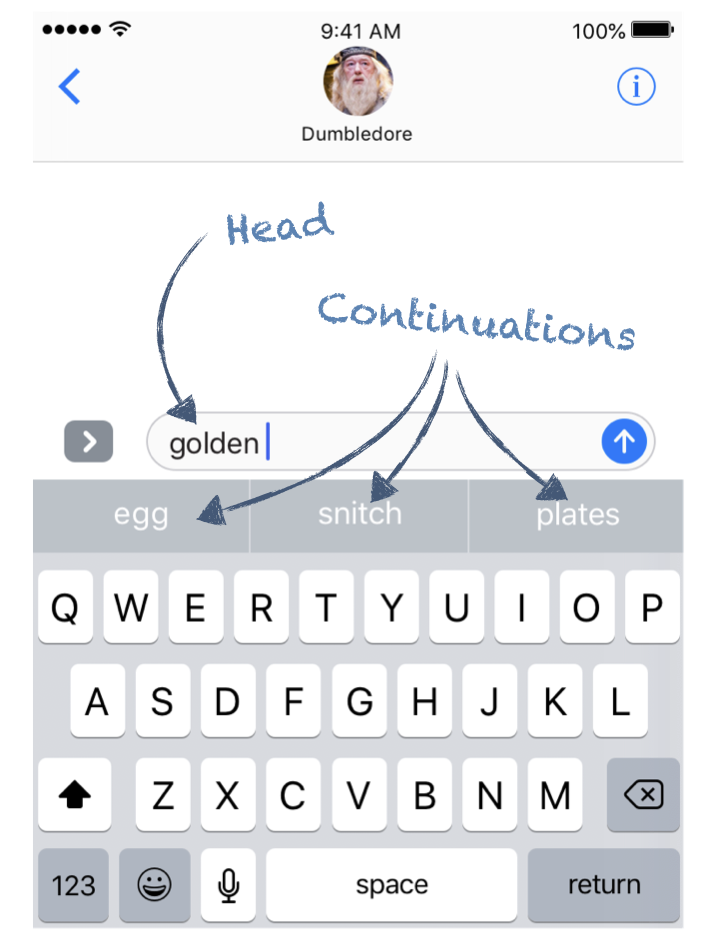

Some terminology that will be useful going forward: I’ll refer to the word which is used as the basis to generate our suggestions as the head or head word, while the suggestions we offer up I’ll refer to as the continuations (since they continue the sentence).

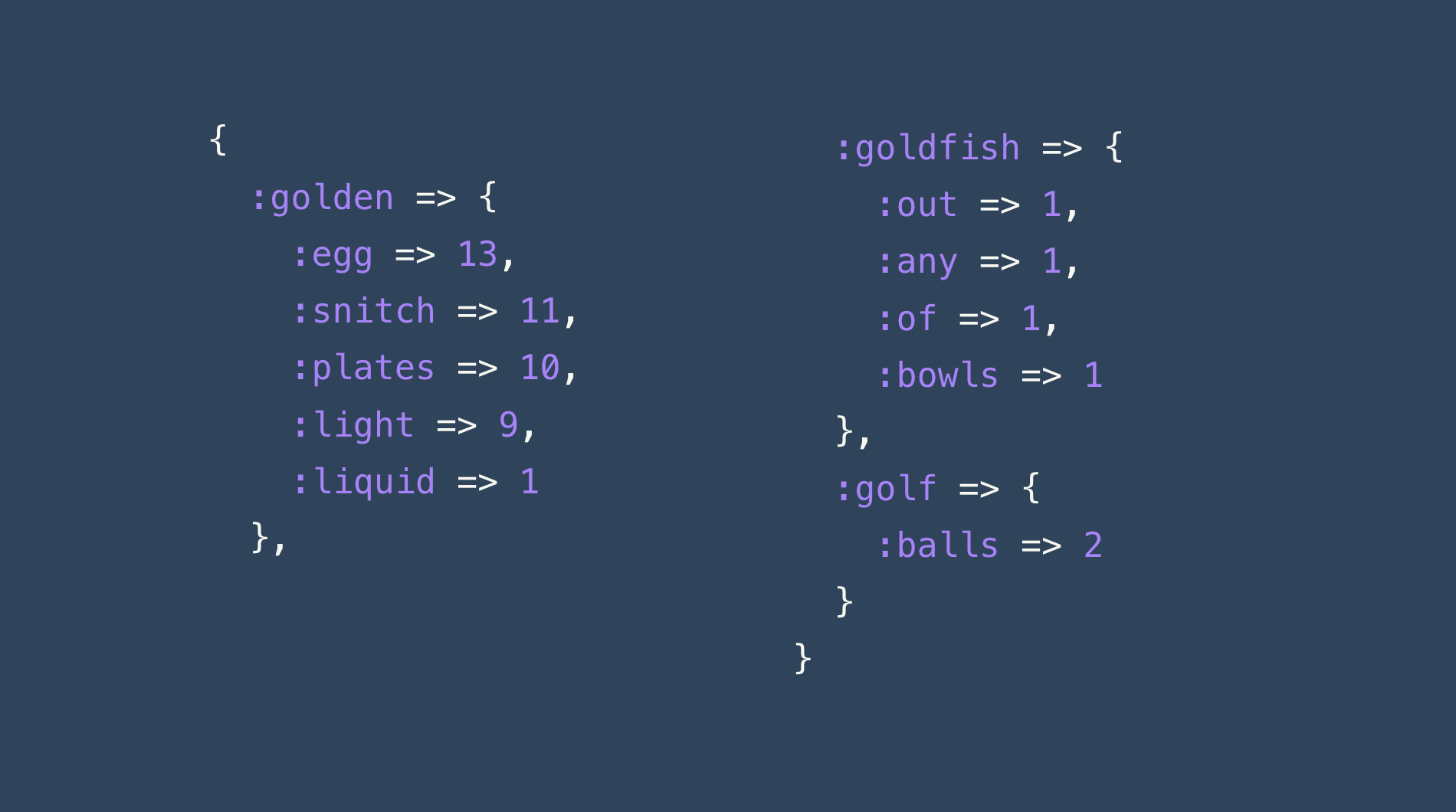

In summary, we need to collect stats for every unique word which appears in the Harry Potter series (by my count, that’s 21,814 words in all), noting each word’s continuations and how frequently they occur. Here’s a snippet of what our final stats data will look like:

Once we’ve collected these stats, and built our imaginary predictive keyboard, we’ll need some procedure to leverage those stats to generate new language. Can we get away with a simple procedure like the one I used in the video above (hammering repeatedly on the predictive keyboard)? Or will we need something more sophisticated? We’ll consider that question shortly, but first, let’s set up our environment and begin by gathering the stats on J. K.’s language usage.

RSpecto patronum

Now we have a , we’re ready to start writing some Ruby (yay 🎉). We’re building what’s known as a language model, specifically a bigram model - the significance of that name will become clear soon.

Tests are going to be invaluable as we’re building our language model, so let’s set up a boilerplate project with RSpec. I personally find Bundler’s bundle gem command very handy for setting up a quick Ruby project, even if I don’t intend for it to be released as a gem.

bundle gem hp_language_model --test=rspec

cd hp_language_model

rm -r lib/hp_language_model

rm hp_language_model.gemspec

echo -e "class HpLanguageModel\nend" > lib/hp_language_model.rb

echo -e "source \"https://rubygems.org\"\n\ngem 'rspec'" > GemfileAccio corpus

Our Ruby program is ultimately going to “learn” J. K. Rowling’s style by ingesting the existing 7 Harry Potter books. This means we’ll need the published books in a machine readable format.

You should definitely legally own a copy of the books before going any further (I mean, if you don’t own copies you should be questioning your life choices in any case 😜). If you do own a copy, compiling a text file like I’ll show below should fall under fair-use (as long as you’re just doing this for your own personal research/tinkering). Of course, I’m not a lawyer and can’t accept any responsibility if you get thrown into Azkhabhan!

Edward Hernández has uploaded an archive of every chapter in .txt format from all 7 books to Github. We can download the chapters, unzip them and concatenate them into a single file like so:

curl https://github.com/syntactician/corpora/raw/master/hp/Archive.zip -L -o hp.zip

unzip -p hp -x .DS_Store __MACOSX/* > hp.txt && rm hp.zipThe concatenated books (hp.txt) will be the raw data we’ll use to shape our model (the Ruby program we’re writing) - we’ll commonly refer to this raw data as our corpus. Before we go any further we’ll want to tokenize our corpus. The tokenizing procedure strips out extraneous details so we can focus on the “meat” of the language we’re working with. We’ll commonly strip out things like case, and special characters. We’ll also store our tokens as symbols, since that’ll save us stats where we have tokens (words) appearing repeatedly (which, of course, will happen a lot). We’ll begin with a simple spec for our tokenization method:

RSpec.describe HpLanguageModel do

let(:corpus) { '' }

let(:model) { HpLanguageModel.new(corpus) }

describe '#tokenized_corpus' do

let(:corpus) {

"Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal"

}

it 'strips out special characters and case' do

expect(model.tokenized_corpus).to eq [:mr, :and, :mrs, :dursley, :of, :number, :four, :privet, :drive, :were, :proud, :to, :say, :that, :they, :were, :perfectly, :normal]

end

end

endFor brevity I’m not taking a purist TDD approach in this tutorial. In real life, you’d want to smaller test cases (e.g. a separate spec for special characters and case), and better coverage of edge cases (what should we get if we pass an empty string to tokenize?).

Here’s a simple implementation of tokenize that will pass our spec:

class HpLanguageModel

attr_reader :corpus

def initialize(corpus)

@corpus = corpus

end

def tokenized_corpus

corpus.downcase.split(/[^a-z]+/).reject(&:empty?).map(&:to_sym)

end

endA bit of arithmancy: calculating our language stats

As we laid out above, we want to begin by going through our corpus word-by-word, a compile a list of every word that occurs, all of its continuations, and how many times each continuations occurs.

For example, given the corpus:

“The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy.”

We’d note:

- Which words appear (“the”, “cat”, “sat”, “on”, “mat”, “was” and “happy”)

- The continuations for each of those words (for example, the word “the” is followed by the words “cat” and “m”)

- How many times each continuation appears (“the” is followed by “cat” twice, and “mat” once).

We can most conveniently store that data as a hash, like so:

{

:the => {

:cat => 2,

:mat => 1

},

:cat => {

:sat => 1,

:was => 1

},

:sat => {

:on => 1

},

:on => {

:the => 1

},

:mat => {

:the => 1

},

:was => {

:happy => 1

}

}Since we know how our stats ought to look, let’s translate that into a spec:

RSpec.describe HpLanguageModel do

# [snip]...

describe '#stats' do

let(:corpus) {

"The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy."

}

it 'encodes the continuations and their counts' do

expect(model.stats).to eq({

:the => {

:cat => 2,

:mat => 1

},

:cat => {

:sat => 1,

:was => 1

},

:sat => {

:on => 1

},

:on => {

:the => 1

},

:mat => {

:the => 1

},

:was => {

:happy => 1

}

})

end

end

endImplementing our stat gathering procedure, and passing our spec is surprisingly simple. We can do the heavy lifting with just a few lines of Ruby code.

attr_reader :corpus, :stats

def initialize(corpus)

@corpus = corpus

build_stats

end

private

def build_stats

@stats = {}

tokenized_corpus.each_cons(2) do |head, continuation|

stats[head] ||= Hash.new(0)

stats[head][continuation] += 1

end

endThe key bit of “magic” here, is the .each_cons method, which steps through each consecutive pair of words. The first word in our pair will be our head, the latter our continuation. If this is our first time encountering this head word, we’ll add it to our stats hash, with an empty hash as its value. However, rather than doing:

stats[head] ||= {}We instead create a hash with a default value of 0:

stats[head] ||= Hash.new(0)That means we can safely call:

stats[head][continuation] += 1Even if there’s no key in the hash for our continuation yet: our program will create the key, set the starting value to 0 and immediately increment it. However, some people find this pattern confusing; feel free to avoid this approach if you prefer, e.g.:

tokenized_corpus.each_cons(2) do |head, continuation|

stats[head] ||= {}

stats[head][continuation] ||= 0

stats[head][continuation] += 1

endWe have all the code to gather the stats on the way J. K. Rowling’s word usage in the Harry Potter, which will form the basis of our imaginary predictive keyboard. Let’s lastly knock together a quick script so we can explore the stats we’ve collected:

require_relative 'lib/hp_language_model'

t1 = Time.now

stats = HpLanguageModel.new(IO.read 'hp.txt').stats

t2 = Time.now

puts "Stats computed in #{ t2 - t1 } seconds"

prompt = "\n" "Enter a word to get stats, or type 'q' to quit" "\n\n"

query = ""

loop do

query = gets.downcase.chomp.to_sym

break if query == :q

next if query.empty?

if stats[query]

continuations = stats[query].sort_by { |word, count| -count }

continuations.each { |word, count| puts "#{word} - #{count}" }

puts "\n" "#{query} appears #{ stats[query].map(&:last).inject(:+) } times in the HP series"

puts "#{query} has #{ stats[query].keys.size } unique continuations"

else

puts "\n" "It doesn't look like '#{query}' appears in the Harry Potter books"

end

endRunning the script, we can Ruby compiles the stats fairly quickly (it takes less than 2 seconds on my Macbook):

Stats computed in 1.170665 seconds

Enter a word to get stats, or type 'q' to quitWe can now type any word to get a nice breakdown of: how many times it appears, its continuations and how many times each continuation was observed:

$ pumpkin

juice - 24

patch - 12

pasties - 4

tart - 1

fizz - 1

plants - 1

next - 1

for - 1

pasty - 1

wafting - 1

pumpkin appears 47 times in the HP series

pumpkin has 10 unique continuationsSomewhat surprisingly, the phrase “magic wand” only appears 3 times in the Harry Potter books, and it doesn’t appear at all in the last 5 books.

The greedy algorithm

“Remember what he did, in his ignorance, in his greed and his cruelty.” — Albus Dumbledore

We’ve gathered our stats, giving us the data we need to produce the suggested continuations for our imagined predictive keyboard in one big stats hash, a portion of which looks like this:

For example, we can see that for the word “golden”, our top 3 suggestions would be “egg”, “snitch” and “plates”, since these are the most frequently observed continuations.

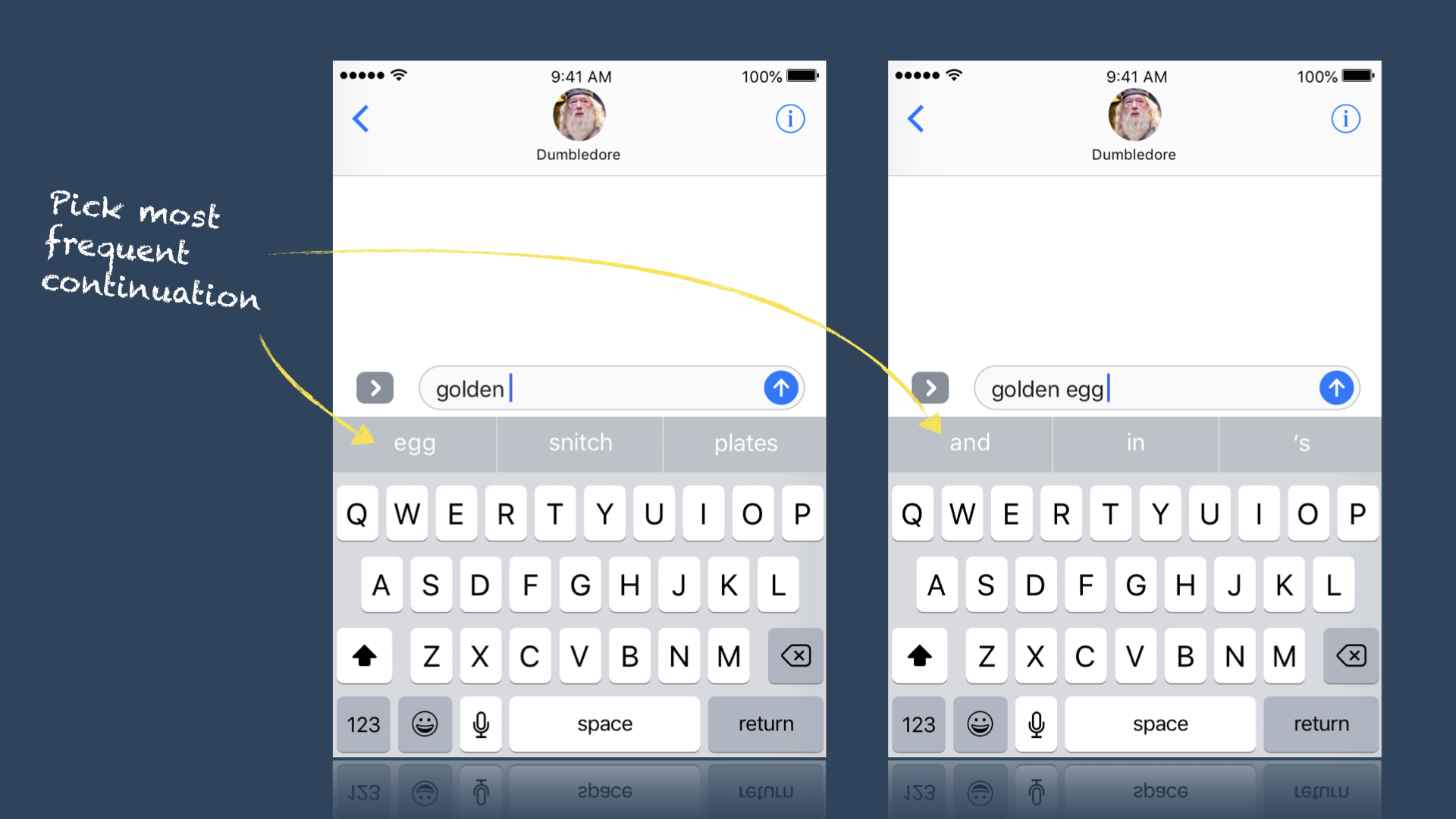

How do we now leverage our suggestions to start generating language? The simplest approach is called the “greedy” algorithm. In the same way a greedy child will always go for the biggest, tastiest treat, the greedy algorithm always opts for the “biggest” continuation, always picking the continuation with the highest observed count.

We already know the word “egg” appears after the word “golden” in the Harry Potter books more than any other word (13 times in all). The greedy algorithm would thus always generate the word “egg” after “golden”. After the word “egg”, the word “and” appears more than any other word; the greedy algorithm would thus always pick “and” as the next word. We can think of the greedy algorithm as the equivalent always picking the first suggestion on our predictive keyboard:

Let’s implement the greedy algorithm. Revisiting our example sentence - “The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy.” - we can see that “the” appears three times; twice its followed by “cat”, once its followed by “mat”. The greedy algorithm should always follow “the” with “cat”. Let’s begin with this assertion:

let(:corpus) {

"The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy."

}

describe '#pick_next_word_greedily' do

it 'always picks the continuation with the highest observed count' do

expect(model.pick_next_word_greedily :the).to eq :cat

end

endImplementing pick_next_word_greedily is straightforward. We have our stats hash tracking every word in our corpus, along with each continuation and the number of times it was observed. Given our previous word, we’ll pick the continuation with the highest count using max_by:

def pick_next_word_greedily(head)

continuations = stats[head]

chosen_word, count = continuations.max_by { |word, count| count }

return chosen_word

endRemember, we’ll generate our spangly new HP story one word at a time, using our stats to generate a successor word based on the previous word in our story. We know have almost everything we need to start generating stories with Ruby, but there’s one last difficulty to overcome. We generate the next word in our story based on the previous word, but then how do we begin our story? (Obviously, the first word has no previous word so our greedy approach won’t work).

Here’s a simple approach: let’s just pick a random word from our vocabulary (e.g. any of the ~22 thousand words which appear in the Harry Potter series) to begin our story. From there, we’ll use the greedy algorithm to extend our story word by word. Let’s add a random_start and generate_story method to HpLanguageModel:

def generate_story(num_words = 50)

story = [random_start] # start with a random word from corpus

1.upto(num_words - 1) do

story << pick_next_word_greedily(story.last)

end

story.join(" ")

end

private

def random_start

stats.keys.sample

endRandomly choosing a starting word makes it a bit tricky to test this method. We’ll look at more robust ways to address this soon (see A bit of Herbology: using seeds for randomness below), but let’s add an optional start argument to generate_story:

def generate_story(num_words = 50, start = nil)

story = [start || random_start]

1.upto(num_words - 1) do

story << pick_next_word_greedily(story.last)

end

story.join(" ")

endNow let’s try generating a simple six word story, starting with “the”, from our example sentence:

HpLanguageModel.new("The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy.").generate_story(6, :the)

#=> "the cat sat on the cat"What happens if we extend the story beyond 6 words? What problem do we uncover?

One nice thing about the greedy algorithm is that it’s deterministic for a given choice of starting word, and if our corpus is small, we can work out by hand what it will output. Let’s translate the test run above into a spec:

describe '#generate_story' do

it 'generates a story of the specified length using the greedy algorithm' do

expect(model.generate_story(6, :the)).to eq 'the cat sat on the cat'

end

endLet’s actually try running the greedy algorithm on the stats gathered from the Harry Potter books. Will we be able to generate a passable Rowling imitation? Let’s create a simple script (say story.rb) in our root directory to generate a story:

require_relative 'lib/hp_language_model'

model = HpLanguageModel.new(IO.read('hp.txt'))

puts model.generate_story(50)Run the script, and witness the… less than stellar results. The first time I ran it, I ended up with this (I’ve added some punctuation but otherwise the output is unchanged):

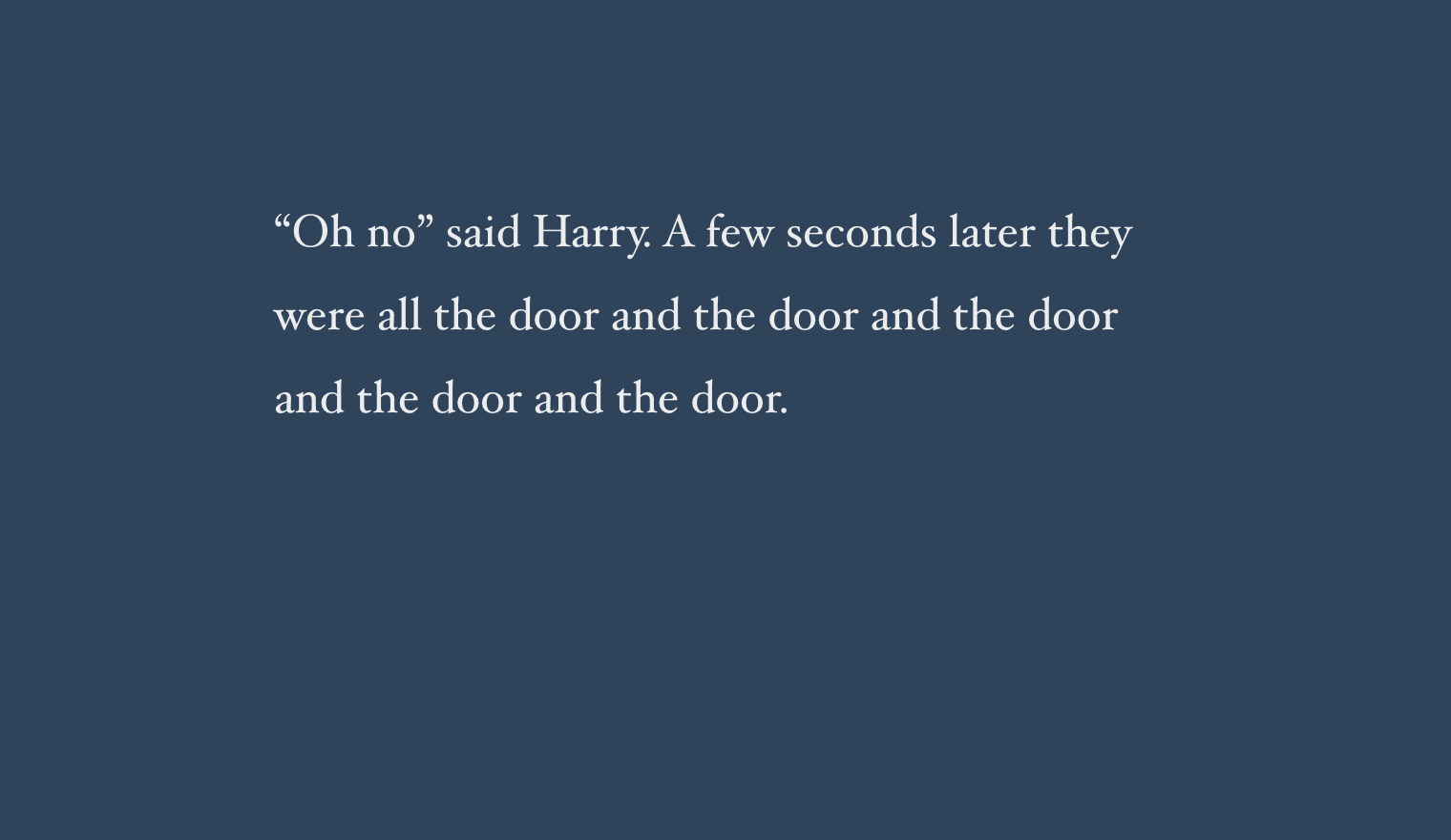

However, maybe we should give our script another chance. After all, we begin our story with a random word, so perhaps our initial randomly chosen starter word just yields an unusually uninspiring story. This was the output of my 2nd run:

Oh no, it’s even worse. Well, at least we know what title we should give our new Harry Potter epic…

Why is the greedy algorithm failing so spectacularly? Let’s add tweak our script to add some debug info. In hp_language_model.rb I’ll add a puts statement to and set a fixed starting word for our story in generate_story:

def pick_next_word_greedily(head)

continuations = stats[head]

chosen_word, count = continuations.max_by { |word, count| count }

puts "Choosing '#{chosen_word}' because it is the most frequent continuation for '#{head}' (appears #{count} times)"

return chosen_word

end

# ...

def generate_story(num_words = 50)

story = [:several]

1.upto(num_words - 1) do

story << pick_next_word_greedily(story.last)

end

story.join(" ")

endLet’s run it and see the output:

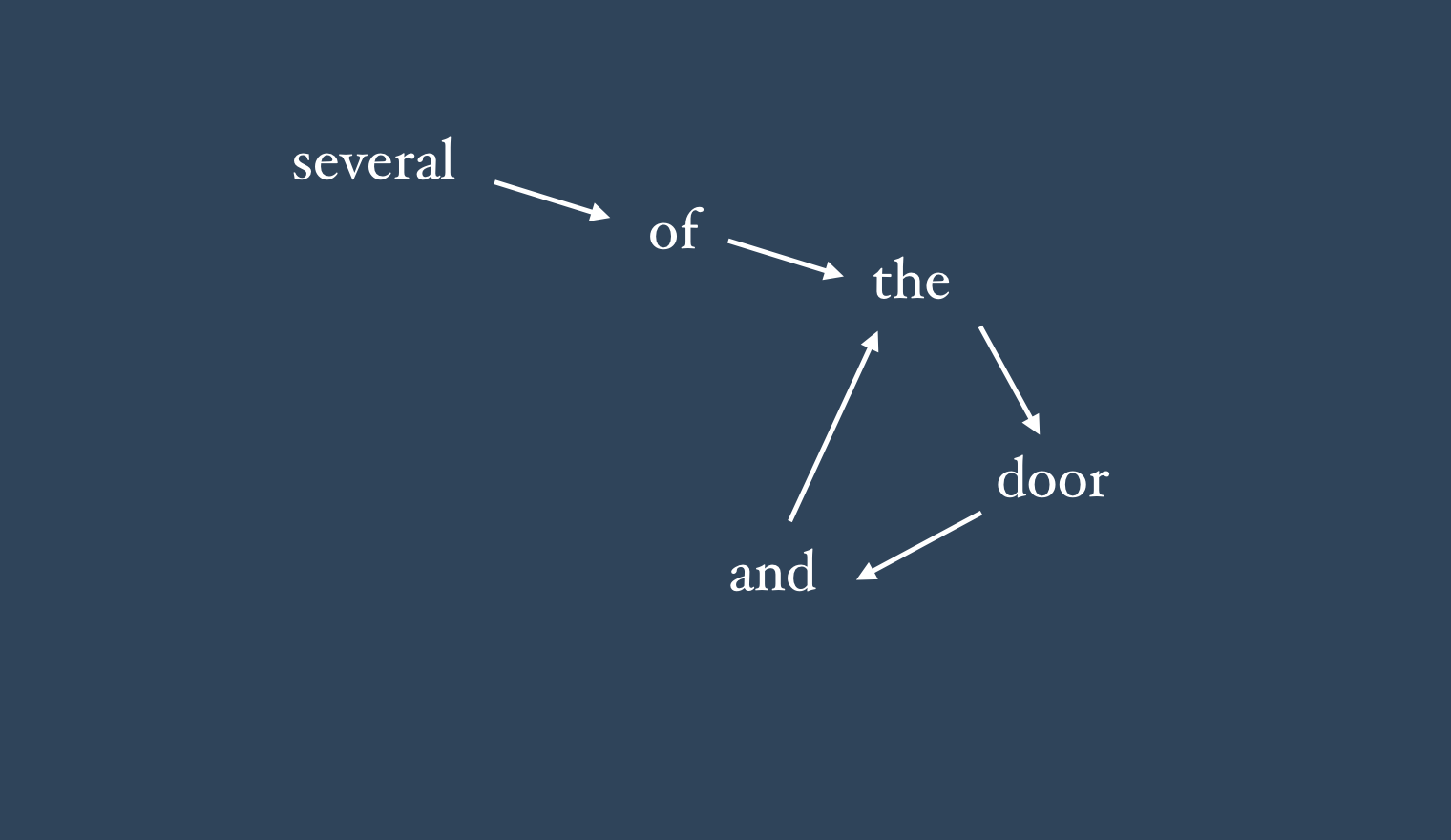

Choosing 'of' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'several' (appears 32 times)

Choosing 'the' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'of' (appears 4924 times)

Choosing 'door' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'the' (appears 792 times)

Choosing 'and' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'door' (appears 132 times)

Choosing 'the' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'and' (appears 1212 times)

Choosing 'door' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'the' (appears 792 times)

Choosing 'and' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'door' (appears 132 times)

Choosing 'the' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'and' (appears 1212 times)

Choosing 'door' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'the' (appears 792 times)

Choosing 'and' because it is the most frequent continuation for 'door' (appears 132 times)Tracing the greedy algorithm’s execution, we can see the problem. “of” is the greedy choice to follow “several” since it’s the most frequently observed continuation in the series (edging out “people” which appears 30 times). “of” is most often followed by “the”, “the” is most often followed by “door”, and “door” is most often followed by “and”. The greedy algorithms choices are thus straightforward in each case. However, we run into a problem, after “and”, because it’s most frequent continuation is “the”. But we all know what happens after “the”! It’s going to take us back down the same path, ultimately generating another “and” and repeating the sequence. We can see this represented visually below:

It’s this tendency to get trapped in cycles which is the greedy algorithm’s fundamental flaw. Does this always end up happening? Unfortunately, yes. The very best we can do is to pick the word “conference” (by an odd coincidence), in which case we’ll get this slightly surreal 20 word sequence:

If that’s the best the greedly algorithm can achieve, I think we can safely rule it out.

Let’s get weird

As they used to say on Monty Python, now for something completely different. The greedy algorithm’s flaw was its overeliance on the observed count of continuations when choosing what word to append to our story. So for our next algorithm, let’s try ignoring the counts altogether.

For this approach, what I’ll call the “uniform random algorithm”, we’ll simply pick a valid continuation (in other words, a continuation which appears at least once) at random. How do we write a test for this? Testing random behaviour is notoriously tricky, but a simple approach is to just run the procedure many times and test that the result falls within some reasonable range. RSpec makes this quite easy with its be_within matcher:

let(:corpus) {

"The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy."

}

let(:num_samples) { Float(10_000) }

describe '#pick_next_word_uniform_randomly' do

it 'picks from possible continuations randomly, with equal probability' do

next_words = 1.upto(num_samples).map { model.pick_next_word_uniform_randomly :the }

expect(next_words.count(:cat) / num_samples).to be_within(0.01).of(1.0 / 2)

end

endThis test asserts that if we have two valid continuations, each should be picked 50% of the time (within a 1% margin of error). Passing the spec is quite easy. For a given head word, we track the continuations (which are the keys in the nested hash) and how many times each occurs (which are the values). We’ll simply ignore the counts, and pick randomly from the continuations using Ruby’s built-in .sample method:

def pick_next_word_uniform_randomly(head)

continuations = stats[head]

return continuations.keys.sample

endWe’ll only need to swap out pick_next_word_greedily with pick_next_word_uniform_randomly in our generate_story method, then we can give it a whirl:

So this is a significantly improvememt over the greedy algorithm, but unless you’re really into avant-garde Harry Potter fan fiction, you’ll probably agree it’s a little odd.

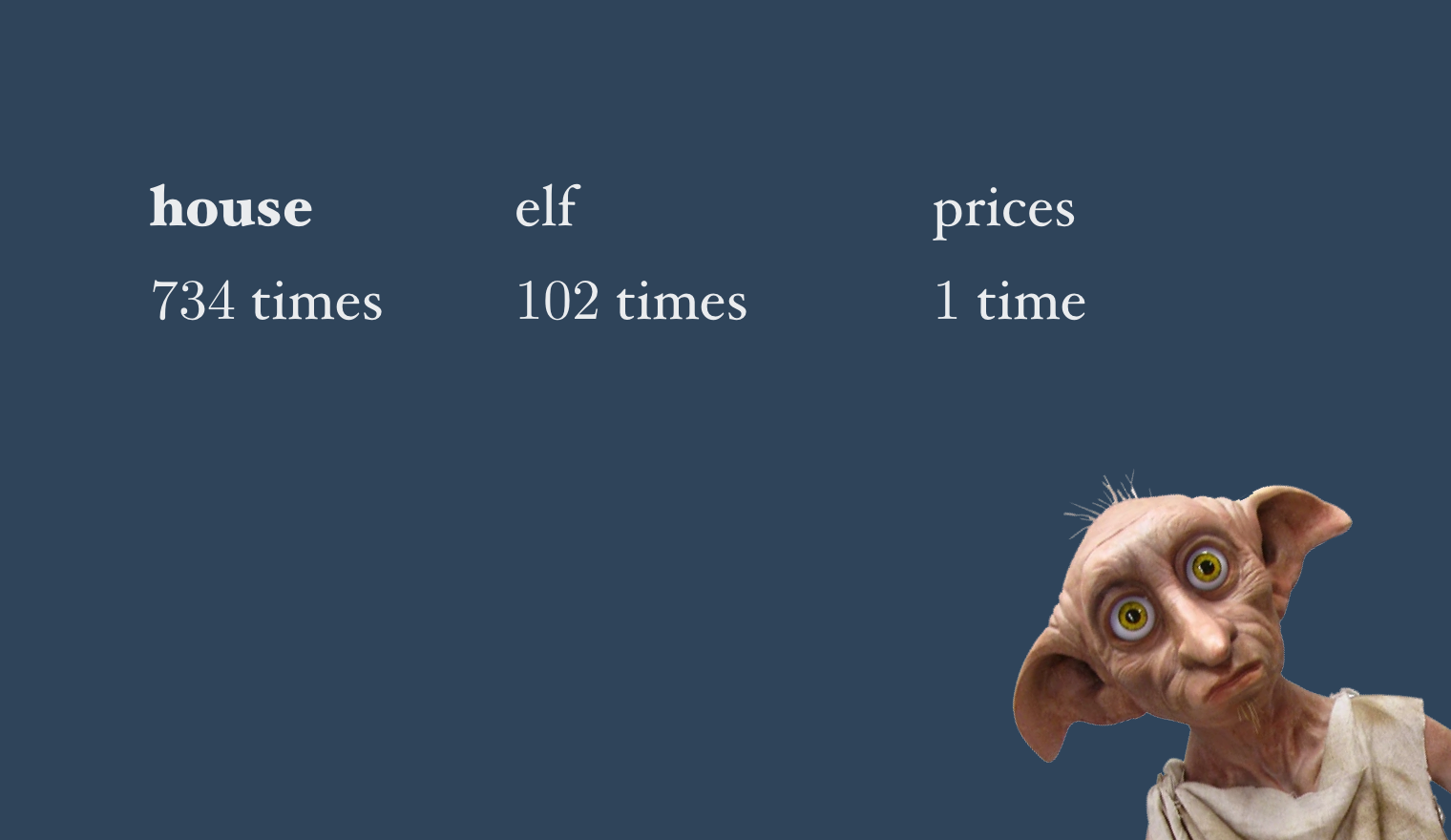

Why is the output from the uniform random algorithm so… weird? One problem is that because we ignore the counts of our continuations, we’re not really doing a great job of imitating the style of the HP books. For example, consider the word “house”:

The word house “elf” follows “house” more than 100 times; in fact, every 1 in 7 times the word house appears it’s followed by elf. In contrast, the word “prices” follows “house” only once in the entire series. However, the uniform random algorithm is equally likely to pick either continuation (about a 1 in 200 chance). Clearly, it’s not ideal for Harry Potter storytelling agent to be equally to write about house prices or house elves…

We can fix this by simplest a weighted random selection algorithm. In this case, we select continuations not with equal probability, but with a probability which is proportionate to how often that continuation appears. With the weighted random procedure, “elf” has a ~1/7 chance of being picked after “house”, while “prices” chance is just ~1/700.

Let’s write a spec for this. We’ll take the same approach as we took when testing the uniform random algorithm, but here we expect that “cat” appears roughly 2/3rds of the time (since “cat” is observed as a continuation twice, while “mat” is only observed once):

let(:corpus) {

"The cat sat on the mat. The cat was happy."

}

let(:num_samples) { Float(10_000) }

describe '#pick_next_word_weighted_randomly' do

it "picks from possible continuations randomly, with probability proportionate to each continuation's count" do

next_words = 1.upto(num_samples).map { model.pick_next_word_weighted_randomly :the }

expect(next_words.count(:cat) / num_samples).to be_within(0.01).of(2.0 / 3)

end

endThe implementation is again fairly straightforward:

def pick_next_word_weighted_randomly(head)

continuations = stats[head]

continuations.flat_map { |word, count| [word] * count }.sample

endLet’s see what’s going on here with a simple example:

continuations = { :apple => 4, :banana => 2, :pear => 1 }

continuations.flat_map { |word, count| [word] * count }

#= > [:apple, :apple, :apple, :apple, :banana, :banana, :pear]We first build a new array, where each element appears a number of times equal to its count/value. Clearly if we randomly sample from this new array, we’ll have a 4/7 chance of drawing “apple”, a 1/7 chance of drawing “pear” - as we desire. Another way of understanding this algorithm is to imagine a raffle, where each continuation gets to enter a number of tickets equal to the number of times it appears. We then draw randomly from the entered tickets.

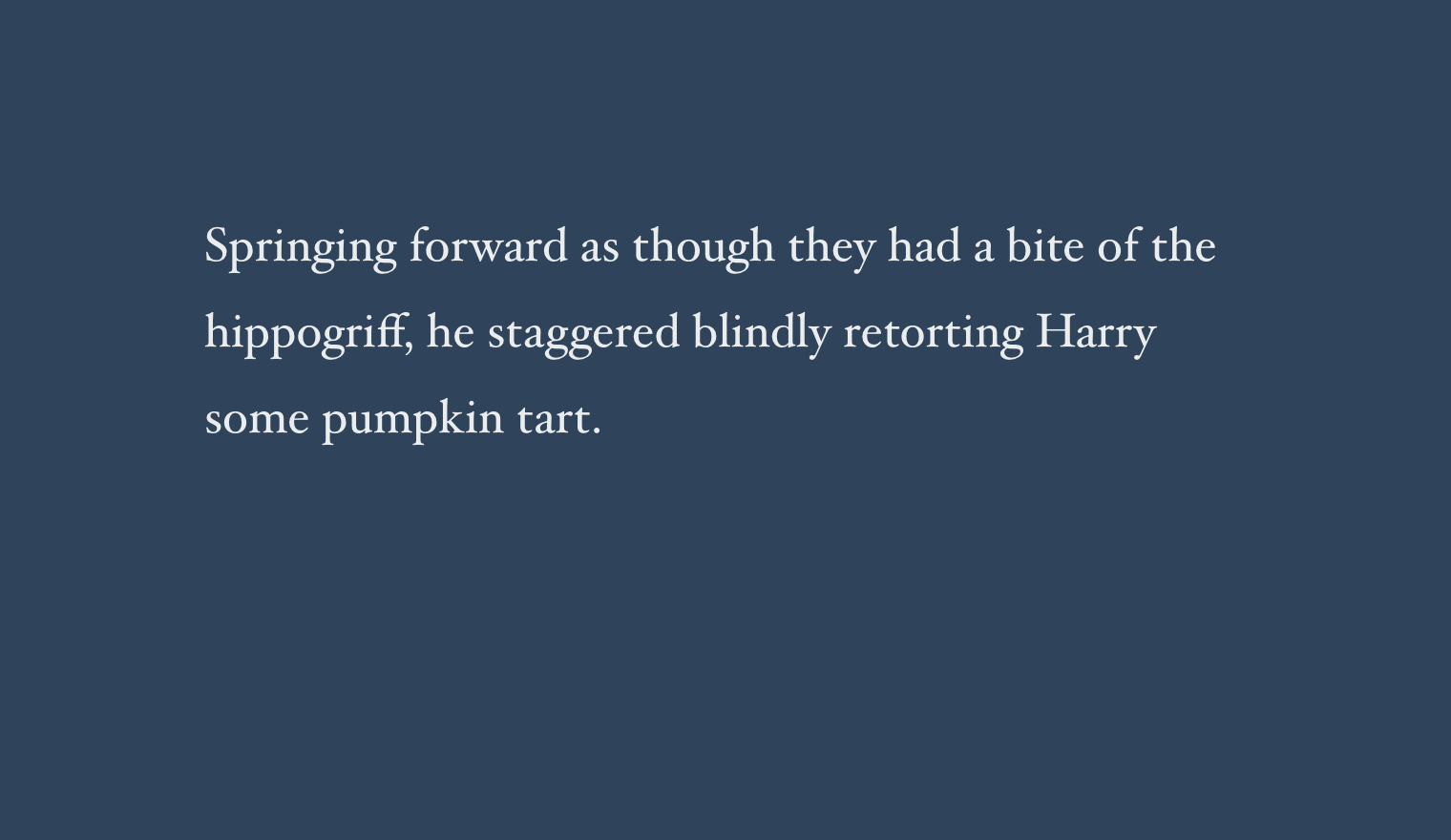

The punchline is that the weighted random approach yields out best output so far:

Higher Order (of the Phoenix) models

(Sorry, that pun was shoe-horned in a bit. Or should I say slug-horned? Oh no, the madness is setting in…)

There’s one last idea that can significantly improve our model’s output. When we examined our smartphones’ predictive keyboards, we noted that they suggest reasonable continuations for the word we just typed. However, if you play around with your keyboard on a modern phone, you’ll find that the story is a little more complicated. For example, if I type the word “and”, on its own, I’m offered these (fairly generic) suggestions:

However, if (as I’m, say, giving my friend some Brighton food recommendations) I type “fish and”, I’m offered a whole other set of suggestions:

Clearly, our phone isn’t just looking at the previous word, but is in fact looking deeper into the sentence. This is the final key idea which will help us significantly improve our model.

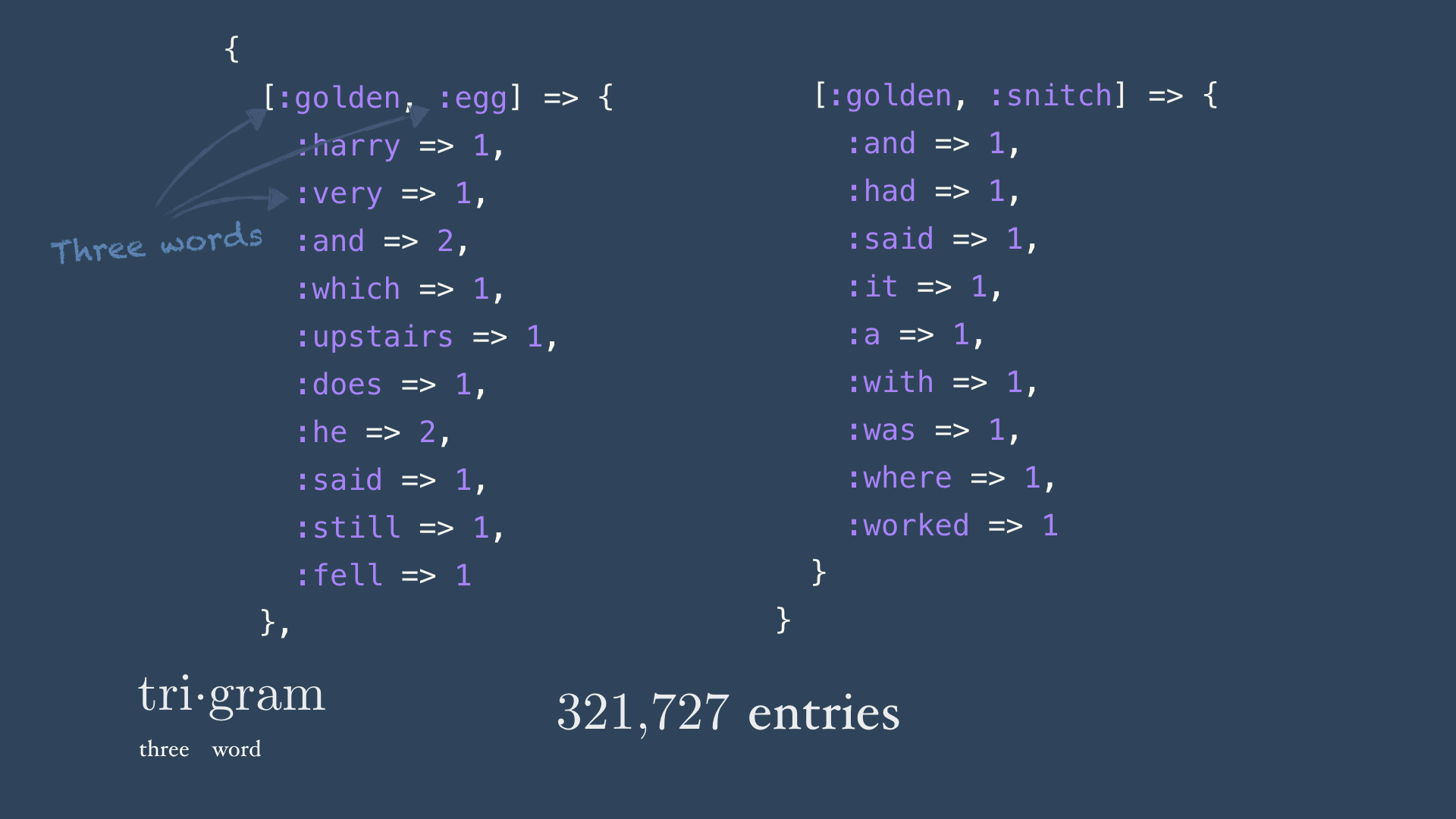

In our initial model, we were effectively always working with pairs of words: a single head word and it’s continuations. We call such a model a bigram model (bigram roughly means “two words”):

We can extend this idea by instead making our head a multi-word phrase. If we look at the previous two words in our sentence, we’ll create a - you guessed it - trigram model. This will mean our stats hash grows: we have 321,727 unique bigram heads, compared to 21,814 distinct head words. We can likewise extend further, to 4-gram models, 5-gram models (usually these are just pronounced “four gram”, “five gram”) and so on; collectively we call these higher order models.

Everything else can more or less remain the same; we’ll still use our same generation algorithm (weighted random selection and so on). Let’s take a look at how we implement our higher order models (it’s surprisingly easy).

A quick sidenote: it’s hard to write a good test for our switch to a higher order model; since a lot of it happens “under the hood”. Although our output will be qualitatively better, that’s hard to test for directly. If we were to test this, it’d be easier to do it coupled with a deterministic algorithm like the greedy algorithm - but for simplicity’s sake I’ll just focus on the implementation.

The first thing we’ll need to do is tweak our collect_stats method:

def collect_stats

@stats = {}

n = 3

tokenized_corpus.each_cons(n) do |*head, continuation|

stats[head] ||= Hash.new(0)

stats[head][continuation] += 1

end

endThe changes needed are surprisingly minimal: first we increase the size of the consecutive chunks we iterate through (in this case from pairs of word to triplets, indicating we’re building a trigram model) and we add a splat to the head block parameter - this indicates that our head isn’t a single word, but it can be a variable number of words (passed as an array). In other words, all elements except the last from each consecutive block for the head and the last element is the continuation:

Let’s move n, indicating the order of the model (n = 2 for bigram, n = 3 for trigram etc.) into an instance variable:

attr_reader :corpus, :stats, :n

def initialize(corpus, n = 3)

@corpus = corpus

@n = n

collect_stats

endFinally, we’ll have to tweak the generate_story method, so that our model is looking at the previous n - 1 words (previous word for bigram, previous 2 words for trigram etc.).

story = random_start

1.upto(num_words - (n - 1)) do

story << pick_next_word_greedily(story.last(n - 1))

end

story.join(" ")That’s it! We can now increase the order of the model, and enjoy the improved results. Here’s an example output from our trigam model:

And our 4-gram model (this is the example we saw at the beginning):

We might be tempted to aggressively increase the order to be much higher - wouldn’t a 10-gram model give us an even better output? The big problem is that as we increase the order too high, we stop diverging from our source text (the Harry Potter books). For example, here’s the output from a 10-gram model:

Sounds great right? The problem is, this is actually a word for word imitation of a section from Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to figure out why this problem arises…

Beyond the veil…

We’ve put together a surprisingly effective language model in just a few lines of Ruby. Where could we go from here? There are several directions we could explore to improve our Ruby program’s storytelling chops.

One limitation of our simple program is how we start our stories: by choosing a word at random from our vocabulary. This words, but the problem is that not all words are apt choices to begin a sentence: starting a sentence with “Harry” or “The” makes sense, but less so for “Said” or “O’Clock”. The solution here is to employ special start and end tokens, which we can add during the tokenization phase:

def tokenize(sentence)

[:'<start>'] + sentence.downcase.split(/[^a-z]+/).reject(&:empty?).map(&:to_sym) + [:'<end>']

endThis requires that we load our corpus as an array of sentences rather than a single blob of text:

This sends us down a bit of a rabbit hole though, because we then need to ensure our text file is formatted so we have one sentence per line. It turns out doing this automatically is more difficult than it might first seems. We might be tempted to do something like:

text.split(".").join(".\n")this naive approach quickly fails however:

text = "Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal."

text.split(".").join(".\n")

#= > Mr.

#= > and Mrs.

#= > Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal.There are a few existing sentence segmentation libraries out there for Ruby which attempt to address these headaches. Pragmatic Segmenter seems very comprehensive but is quite slow, whereas Scalpel is super fast, if less fully-featured.

The good news is that if we are able to segment our text and add our start and end tokens it will allow us to improve our output: we can know start our story with the special :<start> token and Ruby will pick an appropriate continuation. Another advantage is that the addition of :<end> tokens allows us to properly punctuation our story with full stops. (Generally, we’ll strip out the :<start> and :<end> tokens in our final output).

As for other punctuation marks, we have a range of options. The simplest approach is to keep punctuation marks during the tokenization phase; so we’ll have a comma token (:,), a semicolon token (:;) and so on. We’ll want to ensure here that our text file maintains typographical quotes, so we have “ and ” rather than “. Alternatively, we could train a separate model to punctuate our unpunctuated sentence; you can check out Ottokar Tilk’s punctuator project for some great inspiration.

How else could we improve our model? One aspect that we’ve completely ignored is grammar. Many of our generated sentences are ungrammatical. One approach to address this would be to test the sentences we’re generating to test for grammatical correctness, and throw away the ones that aren not. A more ambitious approach would be to try and “repair” ungrammatical sentences.

Another technique we might employ is to intelligently combine multiple models. For example, we might train one model on the narration in the HP books, and train another model on the dialogue. We could then use a state machine to switch between models, as we flip between dialogue narration. Alternatively, we might combine lower- and higher- order models; interpolation or backoff are two common approaches for implementing this. If you’re interested in digging into some of these deeper topics, I’d highly recommend the chapter on Language Models in Jurafsky and Martin’s excellent book Speech and Language Processing (3rd edition).